2.1. The analytical toolkit¶

Tectonics is known to us through its sensible processes of orogeny, seismicity, and volcanism. The energy available to carry out these permutations ultimately derives from the depletion of the thermal gradient of the Earth’s hot interior with space, mitigated to an uncertain degree by internal heat production via radiogenics, core despinning, and other means. Estimates of global heat flow vary from around \(42\) terawatts [Dye, 2012] to upwards of \(47\) terawatts [Davies and Davies, 2010]. Of this power, a mere \(1\%\) is thought to be necessary to account for all the geological activity witnessed on Earth [Turcotte and Schubert, 2014]; if our Earth is a heat engine, it is a weak one.

2.1.1. The Nusselt number¶

A geodynamically rigid planet with Earth’s interior temperature would not be able to access even these modest energies: it would be trapped by its flat, linear conductive geotherm. That the planetary geotherm is evidently much greater than this is evidence that more kinetic processes are at work. The dimensionless temperature gradient is related to the Nusselt number or \(Nu\), the ratio of the measured temperature gradient to the reference gradient, which is the purely conductive geotherm. It can be given in terms of the rate of change of the dimensionless potential temperature \(\theta^*\) with respect to dimensionless depth \(y^*\) [Schubert et al., 2001]:

Where \(|x|_S\) indicates the average value across a surface. The asterisks indicate a non-dimensionalised quantity: this is a convention throughout the literature.

When dimensionless parameters are used - unit mantle thickness and unit temperature range - the conductive geotherm for a non-curved domain is exactly one. Hence, for square geometries, the dimensionless temperature gradient \(Nu\) does double-duty as the heat transfer efficiency: it is the factor by which heat transfer is greater than it would be under a scenario of pure conduction. For curved domains, where the outer length is greater than the inner length, the conductive geotherm is proportionately lesser as it is in a sense ‘stretched out’ across the circumference; letting \(f\) be the ratio of inner to outer lengths (either circumferential or radial), \(Nu\) in these cases diverges from the dimensionless temperature gradient by a factor of \(f\) for cylinders and \(f^2\) for shells. Though harder to measure in practice than in theory, it is implicit that Earth’s Nusselt number must be much greater than one; it is sometimes cited in the order of \(10\) [Tackley, 1996], which is characteristic of laminar (sub-turbulent) flow [White, 1984].

2.1.2. The Prandtl, Grashof, Reynolds, and Rayleigh numbers¶

If conduction is insufficient to explain Earth’s geotherm, another process is implicated, and that is free convection - buoyancy-driven advection of heat. The relative effectiveness of convection is a product of two further dimensionless quantities. The Prandtl number \(Pr\) takes the ratio of momentum diffusivity and thermal diffusivity:

Where \(\mu\) is viscosity, \(\rho\) is density, \(k\) is thermal conductivity, \(c_p\) is specific heat, and the \(r\) suffix indicates a choice of reference value for variable quantities. The Grashof number \(Gr\), meanwhile, concerns the forces involved: it is the ratio of buoyancy to viscous drag.

Without a sufficient Prandtl number, heat will escape from each parcel faster than the parcel itself can be transported by buoyancy, while a low Grashof number would imply that the drag of the medium on each parcel is too great for buoyancy to overcome.

These co-equal terms multiplied give us a third and final dimensionless quantity: the Rayleigh number \(Ra\) or ‘convective vigour’, which is more strictly interpreted as the ratio of the diffusive and convective time scales in the medium; i.e. \(Ra\) serves as the Peclet number for heat. For high values of \(Ra\), convection is much more efficient than conduction for transporting heat, leading to high fluid velocities and flow regimes grading from sluggish to laminar to turbulent. For low \(Ra\), conduction dominates, and the material is largely or totally quiescent. Separating these two domains is an often empirically-obtained value, the Critical Rayleigh Number or \(Ra_{cr}\), which is innate to each fluid; \(Ra\) is sometimes given in terms of \(Ra_{cr}\) as \(r = \frac{Ra}{Ra_{cr}}\). Values of \(Ra\) in most applications can be quite high, and so are usually represented in decimal orders of magnitude; for mantle materials as modelled hereafter, for example, the critical \(Ra\) can be shown to be somewhere between \(10^3-10^4\), with ‘Earthlike’ behaviour scarcely manifest anywhere below \(10^7\) (Chapter 3). Although \(Ra_{cr}\) is often obtained empirically, it can be derived from first principles for certain simple cases, as will be shown.

The Rayleigh number is a powerful tool for interrogating the behaviours of convecting fluids; however, the correct parameterisation of such a heavily compound term is a nuanced affair. Several assumptions are commonly made in the context of mantle circulation which simplify matters at the cost of limiting the scope of validity.

The ‘infinite Prandtl’ assumption asserts that momentum diffusivity is incomparably greater than thermal diffusivity; i.e.:

This is a defensible assumption for the Earth, where the estimated value of the Prandtl number is in fact around \(10^{23}\) [Schubert et al., 2001]. Implied by the above, but worth stating clearly, is that the Reynolds number of the system - the ratio of inertial to viscous forces - approaches zero: i.e. inertia is negligible, present velocity is independent of previous velocity, and turbulence is consequently impossible. (This follows because the thermal Peclet number, which is \(Ra\), must be a product of Pr and Re; hence, to be finite, its expression in terms of Pr and Re must cancel at the limit.)

The infinite Prandtl statement is often taken in tandem with the Boussinesq approximation, which neutralises all density-driven force terms which are not coefficients of gravity; in other words, the fluid is held to be incompressible:

Where \(u\) and \(v\) connote horizontal and vertical velocity components respectively. The incompressibility assumption in two dimensions allows us to define a stream function \(\Psi(x, y)\):

Where \(u\) is the velocity vector and \(\nabla\) is the familiar vector differential operator \(nabla\) or \(del\).

The stream function has many useful properties: lines of constant \(\Psi\) are called streamlines and are everywhere parallel to the velocity vector at that point, and a difference in value between any two points defines the volumetric flux across a line connecting those points, or equivalently the advective flux when multiplied by density \(\rho\). (The absolute value of \(\Psi\), however, is arbitrary.)

In addition to the Boussinesq and infinite Prandtl assumptions, we may further assert that the gravity is always radial and varies only with depth, and also that the fluid is inelastic, i.e. it has no stress memory. Together these several approximations hold wherever a dense, viscous fluid is subject to extreme pressures over relatively large spatio-temporal scales; hence they are held to be broadly appropriate for mantle problems, with some caveats.

With the aid of this toolkit of assumptions, together with the constitutive equations for conservation of mass and energy, it is possible to obtain velocity and pressure solutions for the otherwise insoluble Navier-Stokes equations: the conservation of momentum equations for viscous fluids. The derivation for mantle problems is canonical but lengthy; details can be found in the universally cited textbook literature on the topic [Schubert et al., 2001, Turcotte and Schubert, 2014]. One extremely useful product, however, is a family of robust parameterisations of the Rayleigh number for mantle convection. For a basally-heated system, the following holds:

Where \(\alpha\) is the coefficient of thermal expansion and \(T\) is the temperature drop across the layer thickness \(b\). It may be convenient instead to take the dynamic viscosity \(\nu=\frac{\mu}{\rho}\) instead, in which case:

If the system is internally rather than basally heated - e.g. as a result of radiogenic heating from uniformly distributed isotopes across the mantle - the following instead obtains:

Or, again, in terms of dynamic viscosity:

Where \(H\) is the heating in terms of power per mass. (The expression for \(Ra_H\) relates to that for \(Ra\) by a factor of \(\frac{\rho H b^2}{k}\).)

Of course, in reality, convection in the mantle is driven by both volumetric and basal heating. Unfortunately, there is not yet a universally accepted derivation for such a ‘mixed-heating Rayleigh number’, but one approach which has the virtue of simplicity takes the basally-heated \(Ra\) expression and adds a coefficient which may be interpreted as a non-dimensional \(H\) term:

Where \(H^{*}\) is the specific internal heating rate in W/kg and \({\Delta T}^{*}\) is the dimensionless temperature drop. Because the expression is derived as the quotient of \({Ra}_H\) and \(Ra\), the new \(H\) term may simply be provided as a coefficient of the basally-heated \(Ra\) derivation [Moore, 2008, Schubert et al., 2001].

Because the Rayleigh number so expressed is equivalent to the coefficient of the buoyancy term, it should now be clear why it is often simply dubbed ‘convective vigour’, as that is its primary effect. By parameterising the system in this way, the behaviour of seemingly distinct scenarios can be seen to be related through their common Rayleigh number; what’s more, a dimensionless treatment of the problem can be readily converted to a dimensionalised one by expanding the terms of \(Ra\) with their empirical or inferred values.

2.1.3. Linear stability analysis and the critical Rayleigh number¶

It was hitherto given that the critical Rayleigh number, below which convection is not possible, is typically obtained empirically. In fact, for simple cases such as this of planar basally-heated isoviscous flow, an expression for \(Ra_{cr}\) due to arbitrary perturbations can be derived from the assumptions already held using linear stability analysis. First consider the state of a purely conducting system at thermal equilibrium:

Where \(T_c^*\) is the dimensionless conductive temperature at dimensionless depth \(y^*\); i.e. there is a linear dependency of temperature and depth.

Let us now impose a thermal anomaly \(\theta^{'*}\), uncertain in wavelength and infinitesimal in amplitude:

Where the starred notation indicates a non-dimensionalised parameter and the prime notation, here and henceforth, identifies a perturbation. The choice of \(\theta\) here relates to potential temperature, the quantity conserved along adiabats, which is what this perturbation will ultimately induce.

Before perturbation, the pressure gradient forces were defined solely by the hydrostatic pressure \(p_c\) - the pressure field which is purely sufficient to counteract the force of gravity. After the introduction of the perturbation, but before the resultant perturbed state is realised, the pressure field is modified in two ways: by the buoyancy anomaly of the perturbation, but also by the contribution of the modified density of the parcel to pre-perturbative hydrostatic pressure. Taking this into account, we can define a true perturbation pressure \(\Pi^{'*}\) as:

Where \(p^{'*}\) is the pressure deviation relative to the hydrostatic pressure.

What determines if this seed of chaos shall grow? Equivalently, we may ask which is faster - the growth of the anomaly, or the ambient restoring forces. The answer depends in part on the wavelength of the perturbation and in part on the overall convective vigour of the system; a very lengthy expansion [Schubert et al., 2001] reaches the sixth derivative before delivering the following relation:

Where \(\lambda^*=\frac{\lambda}{b}\), the wavelength of perturbation equivalent to the original anomaly \(\theta^{'*}\) in the horizontal coordinate, expressed as a ratio of the layer thickness \(b\), and \(Ra_{cr}\) is what we came for: the ‘critical’ Rayleigh number above which perturbations of a given wavelength will grow more rapidly than they are diffused. The expression defines a curve through the space of \(Ra_{cr}\) vs dimensionless wavenumber which has a single minimum: this is \(\lambda^{*, cr}\), the wavelength of perturbation at which \(Ra_{cr}\) is at its lowest. Perturbations near this critical wavelength will tend to grow the fastest, since, as it were, they experience the highest ‘local’ Rayleigh number. As it happens, this wavelength, and the minimum \(Ra\) it requires to grow, come to:

At first glance it might seem that we have not truly answered the question of what defines the critical Rayleigh number for a convecting system as a whole, but rather only a contingent answer depending on wavelengths of perturbation. Consider, though, the significance of driving the Rayleigh number below the minimum critical value. This is equivalent to stating that no perturbations at all - not even the least stable ones - are able to grow quicker than the diffusive timescale. At the minimum critical value itself, it follows that only perturbations of \(\sqrt{2}\) scale will grow; this value nonetheless serves adequately as the \(Ra_{cr}\) of the entire fluid, since a perturbation of such a wavelength can always be discovered in any real system - if geometry permits.

Having determined the conditions under which the conductive planform becomes unstable, it behooves us to establish what the new stability criterion must be which now the system seeks. Assuming that the fastest-growing perturbation will ultimately come to dominate all others, what we need is an expression for the velocity field in terms of \(\lambda\) that we can solve for the critical wavelength \(\lambda_{cr}\) [Rayleigh, 1916].

First let us find the infinitesimal thermal anomaly in terms of perturbation wavelength, which must be a sinusoidal function in both \(y\) and \(x\):

Where \(\widehat{\theta}_0^{'*}\) is the first term of the Fourier expansion of \(\theta^{'*}\) and provides the wave amplitude, which is arbitrary.

We can now take the stream function \(\Psi\) in terms of \(\theta^{'}\) and substitute:

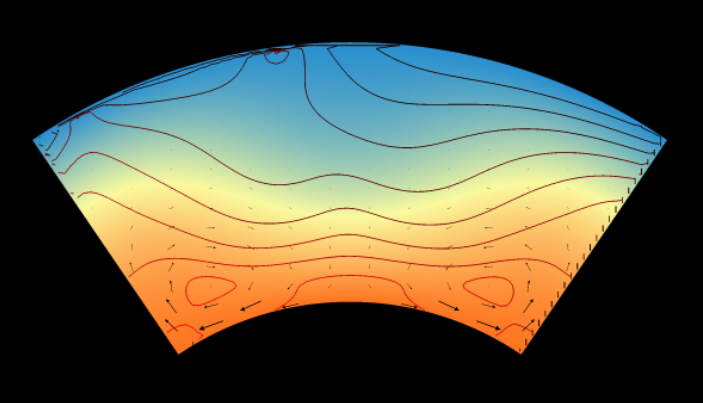

The contours of the stream function give the geometry of convection, which, for the critical \(\lambda\) in two dimensions, takes the form of pairs of counter-rotating half-cells of aspect \(\frac{\lambda^{cr, *}}{2}=\sqrt{2}\); in other words, the planform of convection at steady state for any basally-heated planar isoviscous system will tend to approach an aspect ratio with the approximate dimensions, in landscape, of the page this sentence is written on.

2.1.4. Boundary layer theory and the \(Ra-Nu\) scaling¶

The Rayleigh number by itself is a powerful tool for controlling and dissecting mantle convection models - but it would be better still if \(Ra\), the chief input parameter of the convection, could be analytically related to the Nusselt number, the most important output parameter:

Because \(Nu\) uniquely measures what \(Ra\) uniquely shapes - the convective planform - we know that some function must connect these quantities. To characterise this mystery function, it will be necessary to take what we have learned and delve into the uncertain world of boundary layers.

We have already established that when the Rayleigh number is supercritical, heat may be more rapidly transported by advection than by diffusion. The effect of the ensuing convection is to deflect this conductive geotherm \(T_c^*\) towards the steeper ‘adiabatic geotherm’: the path in temperature-pressure space along which the potential temperature \(\theta\) - that which a parcel would achieve if brought to a standard reference pressure without gaining or losing any heat - is effectively constant. As the abiabat approaches the system boundaries, a point of diminishing returns is reached, and conductive processes take precedence once more. These regions of conductivity are the convecting system’s boundary layers.

It is possible to obtain an expression for the thickness of these boundary layers by considering the linear stability of just the layers themselves. First, we must determine the rate at which the conductive layer expands. This is complicated in the first instance by the fact that the actual layer thickness itself is hard to define in a continuum. Traditionally, however, it has sufficed to define it as the domain across which the first ten percent of temperature is gained or lost. Hence:

Where \(y_T\) is the boundary layer thickness, \(\sqrt{\kappa t}\) is interpreted as the characteristic length scale of thermal diffusion \(\kappa\), and \(\eta_T\) is the inverse error function of \(0.1\), a constant term approximately equal to \(1.16\).

As the boundary grows, so do the thermal buoyancy forces. The relevant Rayleigh number to parameterise the vigour of the incipient convection is taken over the boundary layer thickness itself, and hence grows as the layer grows:

Where \(\alpha\) is the thermal expansivity and \(\nu\) is the dynamic viscosity \(\frac{\nu}{\rho}\).

Now what we are interested in is what the thickness of the boundary layer will be when the Rayleigh number defined over it, \(Ra_{y_T}\), is at its critical value, \({Ra_{y_T}}_{cr}\). Below this value, convective disruption of the layer will not be possible, as any perturbations within the layer will be thermally diffused before they can grow; while above this value, convection is inevitable and the conductive profile of the layer cannot be sustained. The expression for \({Ra_{y_T}}_{cr}\) is the same as that for \(Ra_{y_T}\), except that the temperature contrast \(T\) is half that of the system as a whole; this is because the dimensionless temperature change across either boundary layer goes from zero or unit at the outer edge to exactly \(0.5\) at the inner edge, where the layers face the tepid conditions of the intracellular fluid; so we write:

And accordingly:

Where \(Ra_F\) is coined to refer to the minimum critical Rayleigh number across the layer as defined when that layer is at the brink of collapse.

At this point we might be tempted to define a general critical Rayleigh number for the layer by the same means we deduced one for the system as a whole previously. Unfortunately, the dynamic quality of the layer thickness \(y_T\) poses one unknown too many. For a boundary layer that is developing through time, it is not guaranteed that an appropriate perturbation of the appropriate scale will emerge at the appropriate moment, nor even that the geometry of the layer will ever be sufficient to permit such a perturbation in the first place. We have come as far as analytical methods can take us; to close the loop, it is necessary to obtain RaF empirically:

Where the value \(807\) is the experimentally determined \(Ra_F\) for a free-slip surface [Jaupart and Parsons, 1985].

Now, because the thickness of a conductive layer is directly related to the thermal gradient across it, and thence to the Nusselt number \(Nu\), while the right side contains the coefficients of the global Rayleigh number \(Ra\), it finally becomes apparent what form the relationship between \(Nu\) and \(Ra\) should take:

Or more generally:

That a scaling law of this form would obtain for two dimensionless flow constants such as these is not surprising; empirically, just such a relationship is in fact very widely attested [McKenzie et al., 1974, Solomatov, 1995, Turcotte and Oxburgh, 1969]. Authors have differed, however, on the proper value of \(beta\). Though the canonicity of the analytically-derived value of one third is beyond dispute, it is clear from the divergent results of numerous studies that, in any real scenario, many more variables than we have accounted for must enter the equation. Time-dependence, long-lived thermal heterogeneities, aspect ratio, internal heating, and countless other factors all have a part to play. Obtaining robust scaling laws that account for all these factors is the vexing business of this thesis.

2.1.5. Critical values for the internally-heated case¶

What we have deduced so far is valid only for planar domains with basal heating. This will not suffice if our subject is the real Earth, which is both basally heated from the core and volumetrically heated throughout by radioactive decay.

Consider a convecting system with constant and uniform internal heating. Basal heat will be disregarded. For this analysis it will be necessary to prescribe that the basal boundary is insulating; in other words, while the upper boundary retains a Dirichlet-type fixed temperature condition, the lower boundary must be a Neumann-type condition of heat flux zero. In such a system, we cannot rely on the difference of basal and surface temperature for our linear stability analysis. Instead:

Where, again, \(b\) is the layer thickness, \(H\) is the heating per mass, \(\rho\) is density, and \(k\) is conductivity. The new temperature scale is thus the factor by which temperature must be non-dimensionalised in this treatment. The conducting geotherm must take this into account, and can no longer be expected to be linear:

We now recall the Rayleigh number for internally heated convection, as given previously:

Which, together with the conductive geotherm \(T_c^*\) provides:

I.e. the rate of change of the hydrostatic pressure with respect to depth. Unlike in the basally-heated case, the pressure here is given as dependent on the conductive temperature profile; previously, both temperature and hydrostatic pressure were necessarily linear with depth. From here the analysis proceeds much as in the basally-heated case, only to culminate in an insoluble ordinary differential equation [Schubert et al., 2001] from which only empirical data can recover us:

In other words, for the onset of convection in an internally-heated system with basal-insulating, surface-isothermal, free-slip boundaries, the critical Rayleigh number and characteristic wavelength are both a little more than one quarter greater than for the equivalent basally-heated case.

2.1.6. Chaos and attraction: approximate solutions to insoluble equations¶

The nature of convecting systems in practice ensures that even the simplest problems can be effectively or absolutely insoluble by analytical means. Though we will shortly outline methods for meeting these challenges experimentally, it is always unwise to go too far empirically whither mathematics cannot follow.

One means of probing beyond the insolubility barrier is to take an eigenmode expansion of the equations of state and discard all but the fewest number of terms which still support nonlinear interactions:

Where \(\Psi\) is again the stream function, \(x\) and \(y\) are coordinates, \(\lambda\) is the featural wavelength, \(r\) is the Rayleigh number as a proportion of the critical value \(r = \frac{Ra}{Ra_{cr}}\), and \(A(\tau)\), \(B(\tau)\), and \(C(\tau)\) are time-dependent coefficients which are functions of \(\tau\), time non-dimensionalised by wavelength:

The \(A\), \(B\), and \(C\) coefficients permit a powerful simplification in form. Selecting the appropriate equation from the infinite set contained in the eigenmode expansion [Schubert et al., 2001], the following first-order differential equations can be obtained:

Where \(Pr\) is the Prandtl number, which must be kept finite for this analysis, though it may still be arbitrarily large; \(b\) represents:

These three are the Lorenz Equations [Lorenz, 1963], for which solutions represent states of cellular 2D convection. Because they are severely truncated in form, their scope of validity is limited to low values of \(r\). Nevertheless, they are conceptually extremely useful for characterising the macro-scale character of mantle convection, particularly approaching the point of criticality.

Of the three functions, \(A\) relates to the stream function, \(B\) the resultant temperature variations, and \(C\) a horizontally averaged temperature mode. Three obvious solutions to the system are:

When \(r<1\), the trivial first solution above describes the only stable steady-state solution and represents pure conduction, just as we would expect when \(Ra<Ra_{cr}\). When \(r>1\), this solution becomes unstable, and the only stable solutions become the positive and negative valencies of the second expression above, which represent clockwise and counterclockwise unicellular convection. The ‘choice’ of the system to devolve from the unbiased conductive solution to one of either the left- or right-biased convective solutions is termed a ‘pitchfork bifurcation’, the first of many we will encounter; its existence proves that mantle convection is chaotic.

The two convective solutions above have been shown to be stable - but are they necessarily steady? If we take our two primitive convective solutions further, a characteristic equation can be obtained from which we can derive the following special value of \(r\):

When \(Pr>b+1\), the above expression gives the value of \(r\) above which the two fundamental convective solutions are in fact not stable; in other words, it is the criterion for the instability of steady convection. It is also another kind of bifurcation - a Hopf bifurcation. Around a Hopf point, stable solutions are periodic and cyclical; solutions which cross the bifurcation are hence ‘captured’ by it and cycle through a finite set of states ad infinitum, until or unless those oscillations become great enough to tip a system into the zone of attraction of another Hopf point. Complex paths through phase space can thus be drawn which represent very high-order periodic solutions for the system that resist analytical description. Dubbed ‘strange attractors’, they are the iconic property of chaos theory.

So far, for the sake of argument, we have assumed a finite Prandtl number. This of course contravenes one of the foundational assumptions of our broader analysis. Before moving on, it behooves us to ask whether the chaotic behaviours observed in the Lorenz equations hold in the limit that \(Pr\to\infty\).

This would imply, first of all, that \(A=B\). Hence:

The fixed points of these new equations are the same as for the Lorenz equations, as is the conductive solution when \(A=B=C=0\), which as before is stable only for subcritical \(Ra\); however, the convective solutions can be shown to be stable for all \(r>1\). We might take this to imply that mantle convection cannot be chaotic after all. However, it must be recalled that the Lorenz analysis begins with severe truncation of non-linear terms. For higher-order truncations, it is evident that chaotic phases can exist [Schubert et al., 2001], particularly at high Rayleigh numbers; what is not certain is whether, for a given degree of truncation and a given range of parameters, chaotic behaviours will manifest for a particular system. When we attempt to engage with the problem numerically and empirically through modelling, which is the purpose of this thesis, it will be seen that certain parameter bands are chaotic and time-dependent while others are not; ultimately it will be argued that such zones of chaos represent boundaries in a very high-dimensional phase space, and relate fundamentally to the nature and proper characterisation of tectonic modes.