3.3. Doctrine¶

In devising a solution to the challenges now articulated, it has been useful to think in terms of an abstract doctrine that will now be dubbed ‘Abstractified Knowledge Production’ or AKP.

AKP is an approach to thinking and working within the model sciences. It synthesises elements of the emerging consensuses of the community as previously discussed, but also introduces new ideas and stricter prescriptions. It is both a program for the writing of programs and a theory for the construction of theories. It describes a particular way of thinking and working as a scientist, while also constituting the top-level specification of a software ecosystem that codifies that thinking and facilitates that working. It was created out of necessity to enable a particular body of work and is neither complete nor perfect nor universally applicable. Nonetheless, it is essential to understanding why Everest is designed the way it is.

3.3.1. Why a doctrine?¶

The virtue of a doctrine, as opposed to a theory, is its implicit separation of interior and exterior concerns. Within the scope of inquiries that refer to it, a doctrine has the status of universal truth. Beyond that scope, a doctrine has no status as a theory of knowledge whatsoever, but presents merely as a category to which other concepts may or may not belong. A doctrine permits epistemic closure for depedendent assertions, while still permitting such assertions to access and be evaluated by an external reality via the contingent truth value of the doctrine itself. Whenever a statement is uttered of the form ‘Insofar as \(x\), \(y\)’, we recognise a doctrine at work.

Modern software engineering practices are steeped in a doctrinal way of thinking. Concepts like the separation of concerns, the hierarchical structuring of namespaces, and the pattern of importing and exporting interfaces are all consequences of an imperative to separate the action a program from its implementation. The central idea is that changes in the implementation of one part of the program should not require the updating of any previously valid assumptions made of it by any other part of the program. The body of all the shared assumptions made by agents about each other within a system is the doctrine of that system. That doctrine in turn is all that any external agent needs to know to operate that system successfully.

In the case of a computer program, the outermost doctrine is typically the user interface. This is true for the doctrine of AKP as well, with the exception that the user is not the knowledge producer, but the knowledge consumer. Under AKP, the human participants in a research program are treated as coequal agents in a unified sociotechnical system, whose interior workings are made up of data and analysis pipelines and whose exterior surface is a volume of published and peer-reviewd literature.

It is because of the human element that AKP is called a doctrine, rather than a system. Doctrines, unlike rules or systems, are heeded voluntarily because of their contingent utility in achieving a particular purpose. The particular purpose of AKP is to help knowledge workers to get out of and on top of the sprawling tangle of tools, packages, workflows, and pipelines that sinew the modern scientific method. It is the basis of an ecosystem that aspires to make it easy to do good work well: no more and no less.

3.3.2. First principles of AKP¶

Fundamentally, AKP asserts that knowledge is the mapping of internal to external symmetries.

Already there are some sub-terms that must be explored. The use of the geometric notions of ‘external’ and ‘internal’ implies a boundary of some sort, as well as a privileging of one side of that boundary over the other. The action of ‘mapping’ demands a ledger or record in which those mappings are stored, and thus a set of conventions for reading from and writing to that ledger. Finally, the word ‘symmetry’ invokes the concept of entropy and so situates the interlocutor in a physical realm of time, space, and energy.

3.3.2.1. Examples¶

While it is not epistemologically necessary to further constrain these assertions, it is helpful to think in terms of a more immediate and concrete example, so long as we remain mindful that AKP is not so limited.

3.3.2.1.1. Individual knowledge¶

Consider a human observer, equipped with senses, memory, and the ability to assign symbols to concepts. A boundary enfolds the observer against their will. They realise that they cannot simultaneously hear from one place in space and see from another; neither can they perceive all that they remember, or anticipate everything they perceive. While they may imagine virtually anything, they cannot compel their senses to validate their imaginings. Finally, while they may make observations, and inscribe those observations - or anything else they fancy - within that internal ‘ledger’ that is the mind, they find that those observations and those inscriptions do not have any power in themselves to alter what they refer to. The disjunct between what can be thought and what can be sensed cuts across the universe and separates it into two realms: one that is arbitrary and mutable under willpwer, another that is independent and unresponsive to our wishes. Here is a boundary, two worlds, a ledger, and the potential for symmetry: AKP is now possible.

In this example, AKP can be reformulated: (human) knowledge is the mapping of names to phenomena. An example: the cycle of the sun’s passage through the sky is a phenomenon; it is given the name ‘day’ and becomes knowledge. The assignment of a name (an internal symmetry) to a phenomenon (an external symmetry) moves it from the resilient outer world to the arbitrary inner one, where it can be manipulated, tested, disseminated, disputed, valued, falsified, dismantled, or involved in a higher-level structure: all forms of ‘knowledge work’.

3.3.3. Knodes, Knodules, and the Procedural Encyclopedia¶

To take AKP from a descriptive framework to a useful, working theory of knowledge, it is necessary to define a hierarchy of structures that project the process of knowledge creation into intuitive and actionable terms. Mindful of the original intention of designing and using software for geodynamic numerical modelling, among other emerging applications, it is important that each structure is not only sensible to humans, but also recommends clear and practical algorithmic approaches.

We have defined knowledge as a mapping of symmetries. Under AKP, a mapped pair of this sort is called a ‘knode’, and a collection of related knodes is a ‘knodule’. The assertion that ‘aka’ in Japanese means ‘red’ in English is an example of a knode.

To write a knode down, or inscribe it in human memory, requires that both the reference and the referent be manageably small. We are free to make the reference as small as we like by choosing an arbitrary symbol - but the smaller the symbol, the fewer are available for mapping. As for the referent, the interdependency of things would require any complete description to be the same size as the universe, which would make knowledge impossible. There is no sense in defining knowledge in that way.

In practice, then, we might say that a knowledge binding requires three things:

An arbitrary choice of name,

A ‘path’ pointing from the matters in question to the particular thing being named,

A context which defines the ‘matters in question’ and separates the choice of name from alternative uses of that name ‘out of scope’. Much complexity is elided by that word, ‘context’. In fact, a ‘context’ fundamentally is an elision - of most of the cosmos, usually.

To explore this, consider the compiling of a great encyclopedia. Let us for now assume that we have permission to make our encyclopedia very large if we choose - but still as small as possible. Let us also avail ourselves of an additional structure, the ‘knodule’ - a set of knodes with a shared context. The game is now to minimise the resources needed to store our data by finding the optimal balance between the complexity (i.e. specificity) of the context, and the applicability of that context to as many knodes as possible. The more specific the context, the less memory required to store a particular knode; on the other hand, the more specific the context, the fewer knodes it is appropriate for, and thus the more knodules (and hence contexts) we need to represent everything. This is a challenging problem to solve even when it is well-defined as it has been so far.

The optimal solution will probably be some sort of branching tree of contexts with knodes as leaves. There are two problems with such a model:

Efficiency of compression comes at the cost of lookup efficiency, as it takes more and more time to look up the knodule belonging to the desired context.

The structure is only efficient for what is already included, and must be recalculated in full when even one new knode is added. (The tree is said to become ‘degenerate’.) We may choose any number of strategies to balance these advantages and disadvantages, but any such strategy will necessarily bias the encyclopedia as a whole toward the uses its authors envisage, hindering the progress of knowledge.

What we need is a design for an encyclopedia that is homogeneous and unbiased. Both can be achieved by imposing only that hierarchy which is ‘natural’ to all conceivable knowledge that might be included. Since we have no idea what the universe may contain a priori, but we have a very good sense of our limitations as producers of knowledge, we can achieve both by imposing a hierarchy and nomenclature for our encyclopedia that relates strictly to the procedures of knowledge creation, rather than the products. In other words, we must choose to treat the notion of a ‘context’ as indistinguishable from the notion of a ‘recipe’ - a program for reproduction.

Though such a structure does not entirely liberate us from the problem of efficiently compressing the ‘contexts’ (now the ‘recipes’) as new observational procedures are added, it has the advantage of turning that labour into a virtuous problem - a progressive refinement of the state of the art - rather than a certainly wrong knowledge claim about the universe, which is what a traditional encyclopedia’s table of contents essentially is. Furthermore, common sense would suggest that the growth of complexity of the means of knowing will always be slower than the growth of complexity of what is known, necessitating less frequent and less total restructurings. Organising knowledge in this way also optimises the literature for the use of producers, and immediately suggests ways in which the encyclopedia can be safely partitioned or recombined without jeopardising the means of replicating (and thus validating) its assertions.

Such a volume might be called a ‘procedural encyclopedia’. This is precisely what AKP sets out to support.

3.3.4. Structures of AKP¶

AKP prescribes three top-level structures: the ‘Schema’, the ‘Case’, and the ‘Configuration’. As a rule of thumb:

The Schema is the means of making an observation.

A Case is something observable under a Schema.

A Configuration is an address of an observable feature, quality, or property of a Case.

Together, the three layers comprise a coordinate system pointing from the universe of observables to a particular phenomenon. When that coordinate is bound to a name - an arbitrary symmetry - it becomes that fundamental structure of knowledge, the knode: a mapping of symmetries.

Let us discuss each layer in turn, and see what substructures they might support.

3.3.4.1. Schemas¶

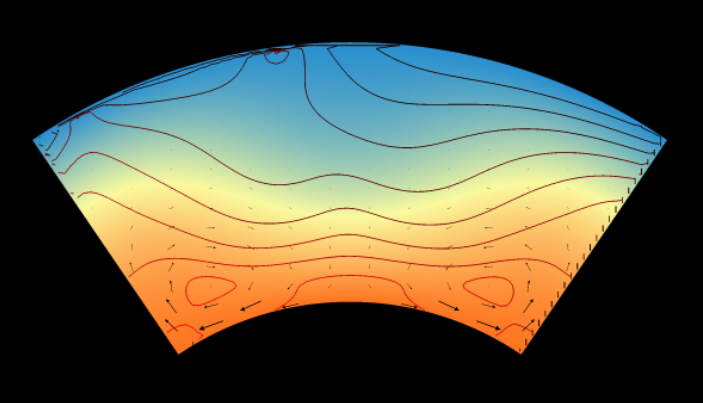

For the notion of symmetry to be ontologically stable, there must be some geometry of observation over which symmetry can be defined. In ordinary life, the consistency of human perception provides that geometry: our intuitive sense of the passage of time and the extent of space, the corporal phenomena of heat and cold, colour and light, and so on. Science, however, has long since surpassed those limitations. Instrumentation has extended the realm of perception, and the symmetries we are looking for are now typically represented as numerical or categorical data instead.

In the parlance of AKP, such a realm is called a ‘Schema’, after Kant [Kant, 1781]. Because a Schema relates to the immediate phenomenological world of humans via the design and operation of scientific instruments, a Schema is defined as a recipe for observational reproduction. The instruction set for building and using a telescope is a Schema; so is the operating code and documentation of a particular computational numerical model.

It will be noted that the top-level structure of AKP concentrates all contextual information in the one layer, the Schema. Naturally, this layer must be compressed, or it will quickly grow unwieldy. Thus, while we have described a Schema as a recipe or instruction set, it is truer to say that it is a ‘meta recipe’ - a recipe for creating a recipe. While the name of the recipe is stable - defined uniquely from the qualities of the instrument assembled by it - the Schema itself actually contains a program for assembling itself based on references to a hidden volume of ‘meta schemas’. Thinking about it in human terms, a Schema might be described as a sort of picture in a craftsman’s mind of what a scientific instrument ‘looks like’. As they learn to make more instruments, the craftsman’s approach to building any particular one might change, but the product will be the same. Of course, Schemas do not have to represent actual material instruments - the subjective experience of colour could be a Schema - but the metaphor is sound.

3.3.4.2. Cases and Schemoids¶

It is tempting, but unwise, to prescribe a Schema with perfect precision. Two telescopes of different makes could be used to make many of the same observations, and two numerical modelling codes may ultimately reproduce the same behaviour. In AKP, these comparable but different models are called ‘Cases’ of a common Schema. A given Schema may contain a potentially infinite range of Cases. To navigate this space, it is helpful to equip the Schema with a finite number of ‘Parameters’. A single Case can then be represented as a vector in ‘Case Space’.

A Schema may be parameterised incompletely - either by assigning some and not all parameter values, and/or by assigning ranges, selections, or other criteria. The effect of such ‘incisions’ on a Schema is to define a kind of subspace in a Schema’s Case Space. In AKP these are dubbed ‘Schemoids’, to emphasise their dependent and spatialised nature.

Disregarding the manner in which it was constructed, a Schemoid should be considered a true Schema in every other meaningful sense. It can be ‘incised’ to yield Cases or Schemoids just as its parent can. Within the overarching Schema of the ‘telescope’, for example, there are many kinds of telescope - reflecting and refracting telescopes, optical and radio telescopes, et cetera. These are all Schemoids of ‘telescope’. Only a complete instruction set for building a given telescope is a proper ‘Case’ of the telescope Schema.

3.3.4.3. Concretions and Configurations¶

A Case as we have defined it is a complete recipe for creating a scientific instrument - but that is not the same thing as the instrument itself. An instantiation of a Case into a given, usable instrument is called a ‘Concretion’ of that Case. Concretions of a common Case can be recognised as such because they are either identical or able to be made identical without permanent alteration. Two telescopes of the same make and brand are Concretions of a single Case, just as are two runtimes of the same modelling code.

Most of the sorts of instruments that interest us have additional degrees of freedom. Telescopes may be refocussed or reoriented; computer programs may receive user inputs or autonomously change their state. Such transformations do not invalidate the shared Case-ness of two given Concretions and thus should not feature as Parameters of their shared Schema. Instead, these inner degrees of freedom are dubbed ‘Configurables’ or just ‘Configs’ of a Concretion - and so of the Case to which it belongs.

Configurables are to Cases as Parameters are to Schemas. A complete set of configurables denotes a unique state or ‘Configuration’ of a Case, such that two Concretions of the same Case that also share the same Configuration are held to be absolutely identical at that moment. Like a Schema, a Case is said to ‘contain’ a vector space of all legal configurations - the ‘Configuration Space’ or ‘Config Space’ - and, like a Schema, a non-strict ‘incision’ of that space yields a subspace, dubbed a ‘Configuroid’.

Deciding which dimensions of a problem to include as Parameters and which as Configurables is somewhat ambiguous. Because two Cases of the same Schema are entirely free to equip themselves with incompatible Configurables, it makes sense as a starting point that any variables shared by all Cases ought to be Parameters. In the end, however - as with any other part of experimental design - a call must be made with the hope of maximising variance across the chosen variables will minimising variance with respect to those elided. For a telescope set to track objects across the sky, it might make sense to consider the instrument’s orientation as a Configurable. For a telescope designed to study the changes of an arbitrary region of the sky over time, it might make more sense to consider the choice of orientation as a Parameter. One must think from the perspective of the controller - human or machine - and consider which variables of the experiment one might wish to have “at one’s fingertips”.

3.3.4.4. States, Controls, and Traverses¶

While all Configurables are equally requisite to define a point in Configuration Space, a distinction can be made between ‘static’ and ‘dynamic’ Configurables.

Consider, again, the example of a telescope. It is pointless to define the Schema of a telescope without including as Configurables the actual circumstances in which a telescopic observation is to be made. These circumstances may include a point on the surface of the Earth to situate that telescope, the orientation or program of orientations of that telescope with respect to the sky, and the time or times of the day and year when the observation is to be taken. If the observation takes place over the course of an evening, or perhaps at the same time of day over the course of a year, then the Configurable representing time is in fact a free variable: the choice of initial condition is static, but after that, the Configuration drifts. Another example might be a beaker of water whose phase space is to be examined. The glass may be brought to a particular temperature, then allowed to equilibrate with its environment. The choice of initial temperature was static, and after that, dynamic.

As a matter of terminology, AKP calls dynamic configurables ‘Statuses’ and static ones ‘Controls’. The set of values of the Statuses at any given occasion is called the system’s ‘State’. When the State is assigned manually, the assigned values are called ‘Initials’ and the full set of them is called an ‘Initial Condition’ or IC; the system is then said to be ‘Initialised’. Any system with one or more Statuses is adjectivally ‘Stateful’, and any system with one or more Controls is ‘Controlled’.

The division between Controls and Statuses suggests a division of Configuration Space into a Control Space and a State Space. While a system may be steered through Control Space arbitrarily at the whim of the experimenter, a State Space by definition has its own natural connectivity: a function of the given Case under whatever Controls are currently applied. Once Initialised, a Stateful system will proceed autonomously according to that connectivity, touching along the way a potentially infinite series of States. Such a series is called a ‘Traverse’ through State Space. A kind of parametric curve defined over a time-like interval, the Traverse construct allows any point in State Space to be named simply using the distance from the nearest known Initial Condition that connects to it.

As more and more Traverses are taken across a State Space, a sense of the latent connectivity of that space is revealed. Assuming that the system is deterministic, that connectivity will have the form of a vector field. To continue the intuitive spatial analogy, that revealed field can be called the ‘Topography’ of the space. Like the vector field defining ‘down’ on a real-life landscape, each point in State Space may have multiple paths connecting to it, but only one connecting from it - though the direction of that outward-bound path may (in the case of ‘ridges’) be infinitesimally divergent.

The distinction between Statuses and Controls need not be prescriptive. It may be a property of the system that a certain Control is relaxed (i.e. becomes a State) after a certain condition is reached; vice versa, a State may be passed back into the experimenter’s hands at certain times, becoming a Control. The distinction may even be placed entirely at the discretion of the experimenter. It makes no difference within the framework of AKP, because it is already strictly enforced that each Case has one, and only one, interior space: its Configuration Space. Within this one master space, all other spaces traversed under a chosen set of control strategies exist together as cross-sections: with each, one builds up a greater sense of the topography of the whole.

3.3.4.5. Knowledge and data¶

AKP asserts that knowledge is a mapping of symmetries: that is to say, an act of identification. It remains to be shown how the structures detailed above facilitate such an act.

Consider Newton’s law of universal gravitation. AKP recognises Newtonian gravity as knowledge because it takes a large class of phenomena, selects a symmetry through those phenomena, and assigns that symmetry a name.

There is an appealingly simple logic to Newtonian gravity that endows it with a sense of ‘truthiness’, but that apparent self-evidence belies centuries of empiricisim. Newton’s gravity is ultimately a unification and generalisation of Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. Those laws in turn represent a symmetry (with error) identified in Tycho Brahe’s observations of the sky - which brings us again to the ‘telescope’.

As it happens, Brahe himself did not make use of the recently invented telescope, preferring naked-eye observation using high-precision versions of the ancient mariners’ instruments: the quadrant and the sextant. All the same, we can identify Brahe as a user of a telescope-like Schema - someone who directed a set of optical instruments at particular parts of the sky at particular times and places and recorded what he saw. There are a number of ways we can construct this in AKP; one might be to say:

Brahe’s Schema was his special system of astronomical instruments - or, more precisely, the complete design and means of operation of them.

Brahe ‘incised’ his Schema with a set of coordinates on the Earth’s surface, yielding a special Case: the Uraniborg observatory on the island of Hven, boasting a full view of the night sky at that latitude.

Brahe then (literally) ‘concreted’ this special case when he built the actual observatory.

Brahe systematically configured and reconfigured the Controls on his observatory while permitting the State of the sky to proceed the under operation of time.

At regular intervals, Brahe wrote down the present configuration of his Controls as well as the value of the traversal variable (the time and date) followed by certain features of the State that interested him - principally, the presence or absence of several stars and planets.

The resultant dataset, under AKP, is synonymous with the one unique ‘path’ that reproduces it. If forward slashes are allowed to represent sub-spaces (‘Oids’) of a particular ‘level’ (e.g. Schemas to Schemoids), and semicolons are set to represent descent to the next ‘level’ (e.g. Schemas to Cases), we might give Brahe’s dataset a name something like:

“Astronomy/ Brahe’s Instruments; Island of Hven; times/ attitudes/ inclinations; planets & stars observed”

Once a dataset is given a ‘true name’ of this kind, the rest is trivial. Kepler’s laws arise as an incision of Kepler’s methods with Brahe’s data, and Newton’s law arise as an incision of Newton’s methods with Kepler’s data. The result is an equation, itself a particular ‘incision’ of mathematics; once obtained, that incision can be embedded in the Schema abstractly governing all objects of mass, where it defines a plane of symmetry that ‘looks like the universe’ - at least until Einstein.

3.3.5. Using AKP¶

In reality, of course, AKP neither caused nor explains the Copernican Revolution. AKP, however, is not a theory: it is a doctrine: an essentially violent imposition whose objective is to coordinate human labour toward a well-defined objective. Its virtue is to recommend a range of practical structures for coordinating the typical daily tasks of a researcher or research team - and by extension, to inform the design of any tools that facilitate or automate those workflows.

At its base, AKP is not much more than a system for uniquely and expressively naming datasets - but there is tremendous power in a name.

3.3.2.1.2. Social knowledge¶

Human knowledge would not have moved very far if it was limited only to individuals: AKP applies to inhuman and superhuman systems too. The boundary around the mind now becomes the boundary around a collection of minds in communication; the individual senses are subsumed within the collective sensorium of the whole community; the ledger becomes a body of shared narratives, spoken or written, giving names to the experience of a people.

Unlike individual knowledge, which is by definition individually comprehensible, the knowledge of a community may easily (and perhaps must necessarily) transcend the scope of what one person can know. Because AKP makes no reference to sentient agents - or agents of any kind - it is not challenged by the notion of a non-thinking system ‘knowing’ things. So long as a system has boundaries, perceptions, and some kind of ledger, knowledge may be held as validly by an AI or, indeed, a sack of Scrabble tiles, as by any thinking thing.

A consequence of this agnosticism with relevance to scientific pursuits is that the academic literature can be thought to not so much contain knowledge as to literally be knowledge. That is why it is so important to ensure that everything that enters the shared ‘ledger’ of the scientific endeavour is properly constructed: that it reflects actual phenomena, that it names things unambiguously, and that it precisely documents itself. The recent replication crisis in several fields shows the consequences of corrupting that ledger. Knowledge can be a desperately fragile thing.