4.2.2. Simple isoviscous rheology¶

Due to their relative simplicity and amenability to symbolic analysis, isoviscous models were among the earliest published mantle convection models [Blankenbach et al., 1989, Jarvis and Peltier, 1986, McKenzie et al., 1974, McKenzie et al., 1973], and they continue to be produced and discussed today [Vilella and Deschamps, 2018, Weller and Lenardic, 2016, Weller et al., 2016, Zhong, 2005].

In an isoviscous model, the viscosity function (usually set to \(\eta=1\)) is constant throughout space and time. Though simple, it is nevertheless able to reproduce appropriate surface velocities, gravitational profiles, and even topographic wavelengths [McKenzie et al., 1974, McKenzie et al., 1973]. Though its parameters are few, there remain limitless possible variations through Rayleigh number, internal heat \(H\), domain geometry, and choice of boundary condition - many of which boast long-term stability solutions with enough implicit nonlinearity to make purely analytical studies infeasible [Daly, 1980]. Even within each parameter set, chaotic dynamics ensure that two nearly identical configurations may yet have wildly divergent outcomes [Palymskiy, 2003, Stewart and Turcotte, 1989]. And while the isoviscous model is certainly the most computationally tractable of all mantle-like rheologies, it is only in the last decade that long-run simulations of appropriate scale for the Earth (\(Ra>10^7\)) have become possible [Trubitsyn and Evseev, 2018, Vynnycky and Masuda, 2013]; these have confirmed earlier intuitions that stable convective planforms may either not exist, or may never manifest, on planetary spatiotemporal scales [Hüttig and Breuer, 2011].

Although the isoviscous model does bely considerable complexity, it is simple enough to make some solutions analytically attainable. Like all convecting systems, a ‘critical’ Rayleigh number \(Ra_{cr}\) should exist below which convection ceases and conduction dominates (i.e. \(Nu=1\)), defining a ‘supercritical \(Ra\)’:

At \(R=1\), perturbations of a certain ‘critical’ wavelength are uniquely able to grow faster than the conductive geotherm and hence become unstable; increasing \(R\) beyond \(1\) makes more wavelengths available for convective growth, until at extreme values (\(Ra >> 10^7\)) even artificial heterogeneities introduced by random noise can grow, such that large-scale models become overwhelmingly time-dependent [Jarvis, 1984]. For a plane domain of infinite horizontal extent, the critical wavelength \(\lambda_{cr}\) should be exactly \(\sqrt{2}\) [Chandrasekhar, 1961], corresponding to a \(Ra_{cr}\) of exactly [Malkus and Chandrasekhar, 1954]:

In any real system, however, \(A\) cannot be infinite, and may be literally or effectively compressed such that the critical wavelength is no longer available. The effect of this is to create a dependency of \(Ra_{cr}\) on \(A\) [Chandrasekhar, 1961]:

At the unit aspect ratios typically modelled, for instance, \(Ra_{cr}\) should instead approach ([Grover and Tandon, 1968]):

A value which is borne out in laboratory testing [Whitehead et al., 2011].

While heat may be transported by convection in the interior of the system, heat may only cross in or out of the system as a whole via conduction. This occurs across two thin layers at the outer and inner boundaries. Since we stipulate that these layers are purely conductive, a Rayleigh number defined only across each layer must be below the critical value for that layer: \({Ra}_{layer} < {{Ra}_{layer}}_{cr}\) Olson1987-do. This is the first observation of boundary layer theory, whence can be deduced the following fundamental power law relationship between the Rayleigh and Nusselt numbers [Schubert et al., 2001]:

Where \(Nu\) is the Nusselt number. The coefficient of proportionality is theoretically \(\approx 0.1941\) [Olson, 1987], though it has been argued that its value will tend be dominated by uncertainty in practice [Lenardic and Moresi, 2003]; reported values have ranged between \(0.25-0.27\) [Jarvis and Mitrovica, 1989, Olson, 1987].

An equivalent scaling [Jarvis and Peltier, 1982] has instead:

Where \(R\), again, is the proportion by which \(Ra\) exceeds \(Ra_{cr}\). Defining \(Ra\) in this way preserves the value of \(\beta\) insofar as \(Ra^{cr}\) is independent of it, but allows the coefficient of proportionality to relate more strictly to non-thermal factors like the domain geometry - for example the aspect ratio, which (above a certain threshold) has been observed to stretch or compress the planform horizontally without changing the underlying boundary stability criteria [Jarvis and Peltier, 1982].

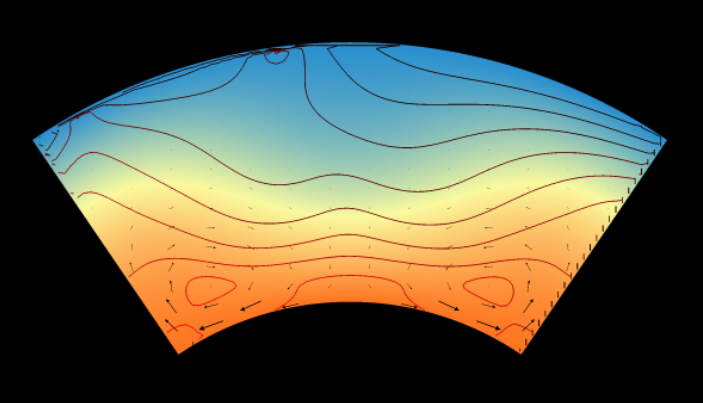

In any case, at the state where \(Nu\) satisfies this scaling, the interior of each cell becomes a homogeneous region of uniform temperature \(T^{cell}\) and variable but low velocities, with strong gradients and shears at the margins, and overall cell dimensions approaching an aspect ratio of \(\sqrt{2}\). Because of the fixed temperature scale, the only way heat transport can be enhanced in such a system is by thinning the boundary layers, which in practice occurs by dripping/pluming until only the theoretical stable boundary thickness is left. For this reason, \(Nu\) also functions as a useful proxy for boundary layer thickness when this is otherwise hard to define.

The canonical beta scaling is seductive because it connects the relatively well-constrained fact of surface geothermal flux with the more mysterious thermal state of the mantle, and so allows parameterised thermal histories to be projected through deep time. The \(\beta \to \frac{1}{3}\) limit itself ultimately derives from the Rayleigh number’s dependence on length cubed, and while there is no a priori reason to believe that this analytical justification must be borne out in practice, it has been recognised as extremely suggestive for over half a century [Chan, 1971]. Testing this scaling behaviour empirically was an early priority of computational geodynamics, with several studies producing estimates that converged on, but did not achieve, the theoretical \(\frac{1}{3}\) scaling: the value has been reported as any of \(0.313\) [Jarvis and Peltier, 1982], \(0.318\) [Jarvis and Peltier, 1986], \(0.319\) [Schubert and Anderson, 1985], \(0.326\) [Jarvis and Mitrovica, 1989], \(0.36\) [Quareni et al., 1985], and \(0.31\) [Niemela et al., 2000], using various methods both numerical and laboratory-based. The reason for the deviation is uncertain. One possibility is that the boundary layer instability theory is only valid in the limit \(Ra\to\infty\) [Olson, 1987]. Alternatively, high \(Ra\) values may witness transitions to alternate scaling logics altogether - perhaps lowering \(beta\) It was for a time suggested that, at very high Rayleigh numbers, an ‘asymptotic regime’ of \(\beta \to \frac{1}{2}\) might emerge, but this has not yet been observed [Niemela et al., 2000].

While the beta scaling strictly holds only for those isoviscous systems with purely basal (no volumetric) heating, Cartesian geometry, and free-slip boundaries, it has been found to hold for a wide range of systems if certain corrections are made.