4.2. Background¶

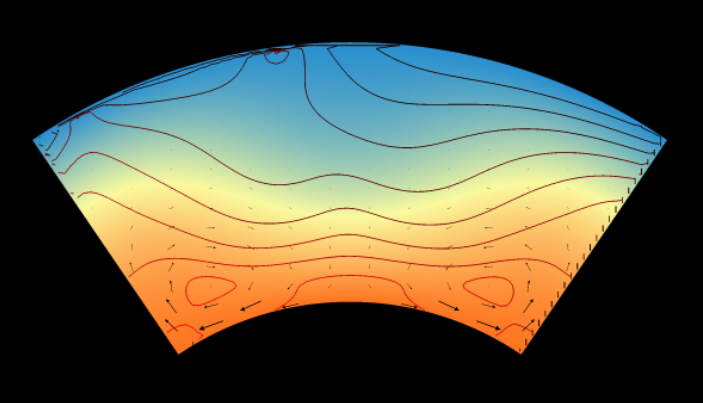

For over half a century now, geodynamicists have accepted that the interior of the Earth and other planets can to some degree be formalised as a variant of Rayleigh-Benard convection amenable to numerical simulation [McKenzie et al., 1974]. While early modelling efforts were focussed on simple rheologies and geometries out of necessity, increasing hardware and software capabilities have since allowed modern investigators to target much more sophisticated behaviours in the search for a truly Earth-like rheology, including strain-rate dependence [Moresi and Solomatov, 1998, Zhong et al., 1998], magmatic history [O'Neill et al., 2018], chemical phases [Tackley, 2012], and more.

The constant drive for increased model complexity comes at the expense of fundamental knowledge of the simpler rheologies which these more advanced systems are ultimately built over: ironic, as modern resources are only now able to support the breadth and detail that early authors would have preferred. There are two major contributors to this ‘complexity preference’ in the modelling literature:

It is easier to argue that a new rheology represents novel work worth publishing.

It is logistically less tiresome to orchestrate a small suite of large models than a large suite of small models.

While there is not much to be done about the first factor, the second factor calls only for effort and invention. It suggests a particular lack of a particular capability: the means to design, operate, and analyse a modelling survey at a much higher level of abstraction.

In this section it will be shown how the state of the art has developed over time with respect to linear rheologies in mantle convection, both in terms of analytical comprehension and numerical simulation. All pre-existing data regarding our parameter space of interest will be reviewed and any shortcoming or contradictions highlighted and discussed. Finally, the question of modelling strategy will be considered, and the essential demands of the problem underlined.