4.2.1. Basics of convection¶

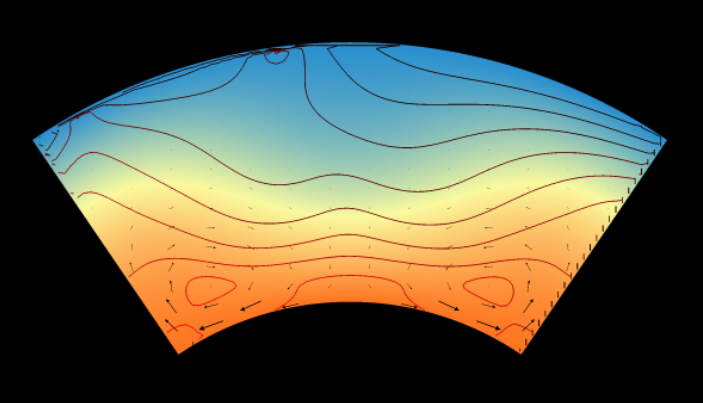

The essential model of planetary solid-state circulation is Rayleigh-Benard convection, in which a fluid held between two plane layers of different temperatures is observed to spontaneously self-organise into counter-rotating cells to maximise the efficiency of transport [Getling, 1998]. Such a model is governed by three principal dimensionless quantities:

The Prandtl number, the ratio of momentum diffusivity (or kinematic viscosity) \(\nu\) to the thermal diffusivity \(\kappa\):

The Reynolds number, the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces and hence a measure of flow turbulence (where \(u\) is flow velocity and \(L\) is a length scale):

And the Rayleigh number, the product of \(Pr\) and \(Re\), interperable as the ratio of buoyancy forces to viscous forces in the fluid (with thermal expansivity \(\alpha\), gravity \(g\), thermal gradient \(\Delta T\), and length scale \(b\)):

In addition to these three input variables, one unifying output variable - also dimensionless - commonly enters into the analysis, and will prove an essential razor throughout this thesis: the Nusselt number, a measure of the efficiency of global thermal transport relative to that expected by conduction alone. It can be given in terms of the rate of change of the dimensionless potential temperature \(\theta^*\) with respect to dimensionless depth \(y^*\) [Schubert et al., 2001]:

Where \(|x|_S\) indicates the average value across a surface. The asterisks indicate a non-dimensionalised quantity: a common textbook convention. This is the definition we adhere to throughout, but there is some variability in how \(Nu\) is defined in the literature. In non-curved domains, \(Nu\) is equivalent to the dimensionless surface temperature gradient, and so it is confusingly defined as such in some contexts [Blankenbach et al., 1989]. There is also a practice of adding a constant \(1\) to the expression, reflecting a difference of opinion over whether \(Nu\) is best constructed as an arithmetic quantity (i.e \(Nu\) as the convective flux after conductive flux is substracted) or as a geometric quantity, as we have stated it here. We prefer the latter usage, reterming the former as \(Nu_{+}\).

Because any convection of interest to us in the mantle is going to be occurring in the solid state, across great distances, and under tremendous heat gradients, we are able to make certain assumptions that simplify the analysis. Two are commonly made:

The Boussinesq approximation, in which non-gravitational terms of density are ignored, with the consequence that the fluid is incompressible. This is a justifiable assumption for just about any non-gaseous fluid, particularly one subjected to such extreme lithostatic pressures.

The infinite Prandtl assumption, in which momentum diffusivity is held to be much greater than thermal diffusivity. This is reasonable for the mantle given the measured value comes to at least \(10^{23}\) [Schubert et al., 2001]. Because \(Pr \cdot Re = Ra\), this also implies that the Reynolds number must be infinitesimal, and hence that inertial forces and the turbulent effects thereof are negligible.

These two simplifications have many consequences. For one, they allow the four dimensionless parameters above to be collapsed to only two: the Rayleigh number \(Ra\) and the Nusselt number \(Nu\) [Turcotte and Oxburgh, 1967]. It will shortly become clear that these two quantities actually bear a power-law relation through a third property, the ‘beta exponent’ \(\beta\), that in a single stroke unifies the intrinsic and extrinsic characteristics of planetary thermal transport:

This elegant law forms the analytical cornerstone of our work.

Though we ground ourselves in theory, our method is empirical. Thankfully, the scheme we have laid out also provides a powerful framework for numericisation: by eliminating inertial, compressive, and turbulent forces, we are able to construct mantle convection as a kind of Stokes Flow under the body forcing of gravity \(g\), limited by conservation of mass and iterated by advection-diffusion, and so captured by the equations:

Where \(\eta\) is dynamic viscosity, \(D\) the strain rate tensor, \(p\) dynamic pressure, \(\Delta\rho\) the density anomaly, \(\mathbf{g}\) the gravity vector, \(\mathbf{u}\) the velocity vector, \(T\) temperature, \(\kappa\) thermal diffusivity, \(t\) time, and \(H\) a thermal source term, i.e. radiogenic heating.

With these equations, we may implement an alternating cycle of instaneous pressure solutions followed by finite time-stepping of the temperature field (and any other state variables we choose to implement). Of course, such a system is meaningless and insoluble unless we further stipulate a geometry (width, length, depth, and curvature) and a set of boundary conditions for the temperature and velocity fields. The boundary conditions on each outer domain surface are typically set to be either:

Fixed in value (a ‘Dirichlet’ condition). For the temperature field, this would imply that the core and/or the space-facing surface of the planet are infinite thermal buffers. For the velocity field, this can be used - for example - to define surfaces that are impervious in the normal component and either no-stick, perfect-stick, or tractional in the parallel component.

Fixed in gradient (a ‘Neumann’ condition): for the temperature field, this would imply that the surface radiates heat at a fixed power, which in the case of zero power would make that boundary effectively insulating; for the velocity field, this essentially configures the strain rate in the chosen component.

With respect to temperature, either of the above conditions can be set to inject or remove heat from the model, which - in tandem with the internal heat function \(H\) - provides the fluid with the thermal situation its flow is expected to resolve, given sufficient time. On Earth, we imagine mantle convection and the interconnected phenomenon of surface tectonics to represent the Earth’s own natural solution, or solution-in-progress, to the circumstance of volumetric radiogenic heating and basal heating from the core, although the debate over the relative significance of these is ancient and ongoing [Gando et al., 2011, Huang et al., 2013, Jaupart et al., 2015, Korenaga, 2003, Korenaga, 2008, Mareschal et al., 2012, Thomson, 1862, Urey, 1955]. For the models being discussed forthwith, we have restricted ourselves to free-slip velocity boundaries and Dirichlet thermal boundaries with a constant unit temperature gradient from top to bottom, such that the heating regime is always either purely basal or mixed.

Within these simplifying constraints, almost limitless variety is possible - which is why this essential formulation has become common to virtually all studies of mantle convection. However, while it is hoped that somewhere within problem-space a solution resembling Earth may be found, such a solution must elude us until our grasp of the fundamentals is absolute; and there is still much about even the simplest rheologies that we do not understand.

4.2.1.1. Linear rheologies: the isoviscous case¶

When we talk about rheology, or a materials’ style of flow, we are primarily talking about its viscosity function - the expression that maps the local viscosity at any point in the fluid to its context, history, or environment. While most fluids in the real world have complex ‘Non-Newtonian’ rheologies in which pressure and viscosity are co-dependent, mantle convection studies have often relied on simpler Newtonian rheologies that are more numerically and analytically tractable. These are what we here call ‘linear rheologies’.

The bulk of all mantle convection studies focus on one of the following three linear rheologies:

Isoviscous or ‘constant viscosity’ flow.

Arrhenius-type exponentially temperature-dependent viscosity.

Spatialised viscosity - either arbitrarily zoned or simply depth-dependent.

This two-part investigation will focus on the isoviscous and Arrhenius types. The former can be viewed as a special case of the latter, so it makes a fitting launching-off point for this study.